Injury prevention for runners

Getting the Balance Right for Runners

Running looks simple, but in reality it is a highly coordinated skill that places repeated demands on the same joints, muscles, and tissues thousands of times per run. Because so many muscles are involved, and because running is repetitive by nature, even small imbalances around a joint can gradually increase stress and raise the risk of injury.

At Weaver Physio, Specialist Running Physiotherapist Richard Mason explains why improving balance, strength, and coordination throughout the body is essential—not only for injury prevention, but also for running efficiency and long-term performance.

Why Balance Matters in the Human Body

Every joint in the body is designed to move in specific directions, and every movement has an opposing counterpart. For movement to be efficient, the muscles that create and control these movements must work in harmony.

Muscles move joints through a carefully timed combination of:

• Contraction (to produce movement)

• Lengthening (to control and decelerate movement)

When this balance is disrupted—often through repetitive postures or activities—certain muscles can become overactive and tight, while their opposing muscles become lengthened and weak. Over time, this imbalance alters how forces travel through a joint, changing movement patterns and increasing tissue stress.

If left unaddressed, these altered mechanics can contribute to pain, overload, and injury.

Running: Repetition, Load, and Technique

Running is a dynamic, single-leg activity that transfers body weight from one limb to the other in a continuous cycle. It is an excellent way to develop cardiovascular fitness and strengthen muscles, tendons, and bones.

However, unlike many sports, most runners are never formally taught how to run. Instead, running technique develops naturally over time—often influenced by lifestyle habits, posture, previous injuries, and strength deficits.

Unless someone has exceptionally efficient natural mechanics, subtle biomechanical faults can build up gradually. These may not cause immediate pain, but over months or years they can lead to:

• Muscular imbalances

• Postural changes

• Reduced efficiency

• Increased risk of overuse injury

Common Running Technique Issues

Upper Body Contributors

Although running injuries often present in the legs, upper body position plays a key role in efficiency and load distribution.

Common upper body faults include:

• Forward head posture, placing strain on the neck and upper spine

• Looking down at the feet, increasing tension through the neck and shoulders and encouraging forward trunk lean

• Rounded or slouched shoulders, often linked to prolonged desk-based work and tight chest muscles

• Arms swinging across the body, rather than forwards and backwards in the direction of travel

• Excessive tension through clenched fists and shoulders

• Poor trunk control, often due to reduced core strength

These issues can subtly increase energy cost and alter lower-limb loading.

Lower Body Contributors

Lower body mechanics play a central role in injury risk.

Common contributors include:

• Pelvic drop or excessive pelvic movement, often due to reduced hip stability

• Anterior muscle dominance, where hip flexors and quadriceps overpower weaker gluteal muscles

• Over-striding, where the foot lands too far in front of the body, increasing braking forces

• Reduced ankle mobility or stability, limiting shock absorption and propulsion

Each of these factors increases cumulative stress on joints and soft tissues over time.

How the Lower Body Works During Running

To understand why imbalance matters, it helps to look at how muscles work together during the running cycle.

At push-off, the calf muscles contract to drive the body forward while the gluteus maximus extends the hip and the quadriceps straighten the knee. As the leg leaves the ground, the hamstrings bend the knee to bring the heel upwards, followed by the hip flexors swinging the thigh forwards.

As the leg prepares for contact, muscles at the front of the shin lift the foot, positioning it for landing. On impact, a coordinated group of muscles work together to absorb load:

• The ankle stabilisers control foot motion

• The quadriceps manage knee loading

• The hip stabilisers—particularly the gluteus medius and minimus—keep the pelvis level

Once the body weight moves over the stance leg, the cycle repeats.

If any link in this chain is weak, tight, or poorly coordinated, load shifts elsewhere—and injury risk rises.

Why Muscle Imbalances Increase Injury Risk

Most running injuries are classified as overuse injuries, meaning they result from repeated micro-stress rather than a single traumatic event. This risk is significantly higher when muscles around a joint are not working in balance.

Strength deficits, reduced flexibility, and poor control all contribute to how load is distributed. When tissues are repeatedly overloaded beyond their capacity, pain and breakdown follow.

Key Areas Where Imbalance Commonly Occurs

Hip Muscles

Modern lifestyles involve prolonged sitting—at desks, in cars, and on sofas—placing the hips in flexed positions for much of the day. Over time, this can shorten hip flexor muscles.

When tight hip flexors are combined with the demands of running, the body can struggle to generate effective hip extension. This limits gluteal activation, causing the glutes to weaken and the running pattern to become dominated by muscles at the front of the body.

This often results in a shorter, shuffling stride and reduced propulsion.

Injuries commonly associated with this pattern include:

• Iliopsoas tendinopathy or bursitis

• Rectus femoris strains

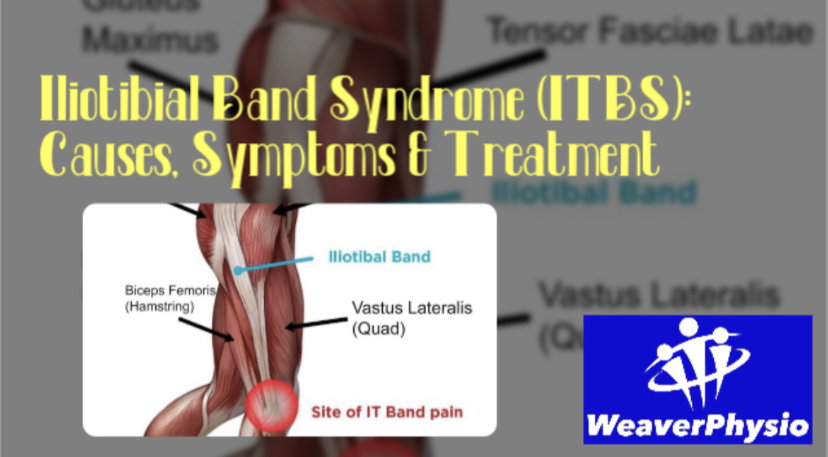

• Iliotibial band–related pain

Knee Muscles

When anterior dominance continues down the chain, tight quadriceps can limit the effectiveness of the hamstrings. This imbalance alters knee loading and increases stress through the front of the joint.

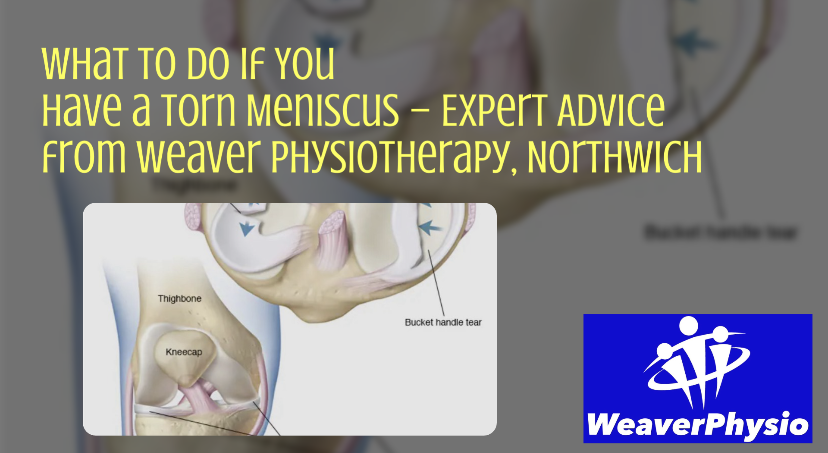

Common knee-related issues linked to imbalance include:

• Patellofemoral pain (runner’s knee)

• Patellar tendinopathy

• Fat pad irritation

• Hamstring strains due to reduced strength and load tolerance

Ankle and Foot Muscles

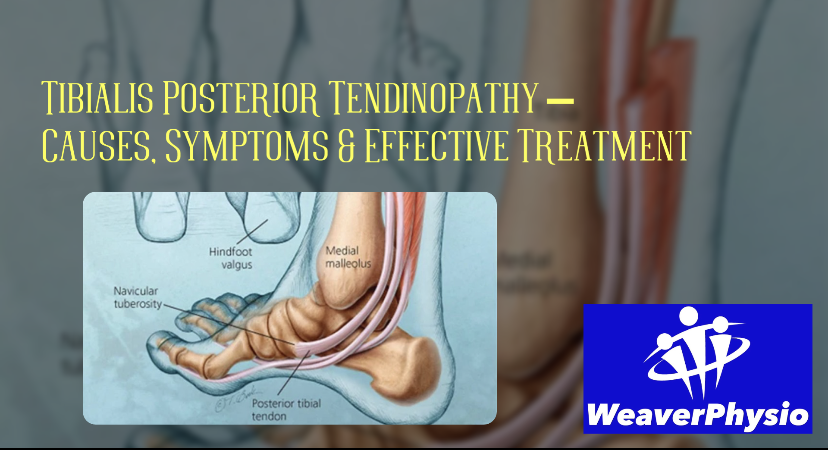

At the ankle, the calf muscles and shin muscles work as opposing pairs. Reduced calf flexibility limits ankle movement, increasing stress through the Achilles tendon.

The muscles of the foot play a vital role in shock absorption, stability, and propulsion. Weakness here often leads to excessive foot collapse (over-pronation), forcing the calf muscles to work harder to stabilise the limb.

Over time, this increases traction forces through tendons and bony attachments.

Imbalance-related conditions in this region include:

• Shin pain and stress fractures

• Plantar fasciitis

• Tibialis posterior overload

• Calf strains

• Achilles tendinopathy

What About Running Style and Foot Strike?

Much attention has been given to forefoot and midfoot running styles compared to heel striking. While certain strike patterns may reduce ground contact time and improve elastic recoil, they also increase demand on the calf–Achilles complex.

Without adequate strength, flexibility, and foot stability, sudden changes in running style can increase injury risk rather than reduce it.

The key message is not about copying a specific running style—but ensuring the joints and muscles are balanced and capable of handling the demands placed upon them.

Final Thoughts: Balance Is the Foundation of Injury Prevention

Efficient running relies on strength, flexibility, control, and coordination working together across the entire body. When one area underperforms, another compensates—and injury risk increases.

By addressing muscular imbalances, improving movement quality, and strengthening key areas, runners can:

• Reduce injury risk

• Improve efficiency

• Enhance performance

• Enjoy longer, more consistent training

About Richard Mason

Richard Mason is a Specialist Musculoskeletal Chartered Physiotherapist and Specialist Running Physiotherapist based in Northwich, Cheshire. He has completed over 1,000 detailed biomechanical running and gait assessments, using advanced video analysis to identify movement inefficiencies, training-load errors, and injury risk factors.

Richard regularly treats complex and persistent running injuries including Achilles tendinopathy, plantar fasciitis, medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splints), runner’s knee, IT band syndrome, hamstring injuries, and stress-related bone injuries—guiding runners safely from diagnosis through to full return to running.